This post was updated February 2020 to include better organization, fresh graphics, copyediting, and updated resources. Did I mention it's way better now? If you're looking for more on the pelvis, find our overarching movement philosophy and how it relates to pelvic issues, as well as more pelvis and pelvic-floor articles, exercises, and recommendations at Our Best "Healthy Pelvis" Resources.

Joan: OMG Becky, look at that back. It’s so sway.

Becky: I know. Why they got to go around sticking that thing out?

Joan: I know. They've probably got a lot of back pain too, ya know? Yeah. They need to tuck. that. thing. under. Ya know?

Becky: Yeah. I know what you mean.

Alignment and anatomy-lovers, which of the following terms accurately describes what's going on in the image above?

A. swayback

B. anterior-tilted pelvis

C. hyperlordosis of the lumbar spine

D. hyperextension of the lumbar spine

D. all of the above

Let's start with "it's not all of the above." Because it isn't. All of the above.

One correct answer is, A: Swayback, and that's because swayback doesn't mean any one particular thing; it's just how spinal curvature looks to the eye—hollowed out a bit. Swayback shouldn't be used clinically as it doesn't have a precise definition (read: it doesn't tell you anything definitive about one's pelvis or lumbar spine.)

Answer B is incorrect; the person in the picture (oh wait, that's me!) actually has a neutral pelvis. How do I know? I know this because I purposely put my body in this position for the picture.

Neutral pelvis

Typically, I’m not a fan of neutral. I never paint my walls Swiss Coffee. I’ve never been to Switzerland. My car (and my mind) are almost perpetually in gear. I am, however, a huge fan of neutral pelvis. "Neutral pelvis" is an often-used term, but even amongst anatomy-using professionals, the definition can get pretty vague. Below I'll define how I use it.

Technically (and let’s be technical, shall we?), neutral pelvis refers to the three-dimensional position of the pelvic girdle and how it relates to the ground and to other body parts.

Front view

The first two planes of “neutral” can be determined by placing your hands on the top, body protrusions of the pelvis, your two Anterior Superior Iliac Spines (ASIS)—often (and incorrectly) called the “hip bones.”

Stand in front of a mirror to see if these points are level, like the artificial horizon on an airplane.

Top view

Looking down to your pelvis from above, check to see if each ASIS is equally out in front of you. One half of your pelvis should not enter the room before the other. This is a difficult alignment to maintain if you are a salsa dancer or are particularly fond of twisting your hips when you walk.

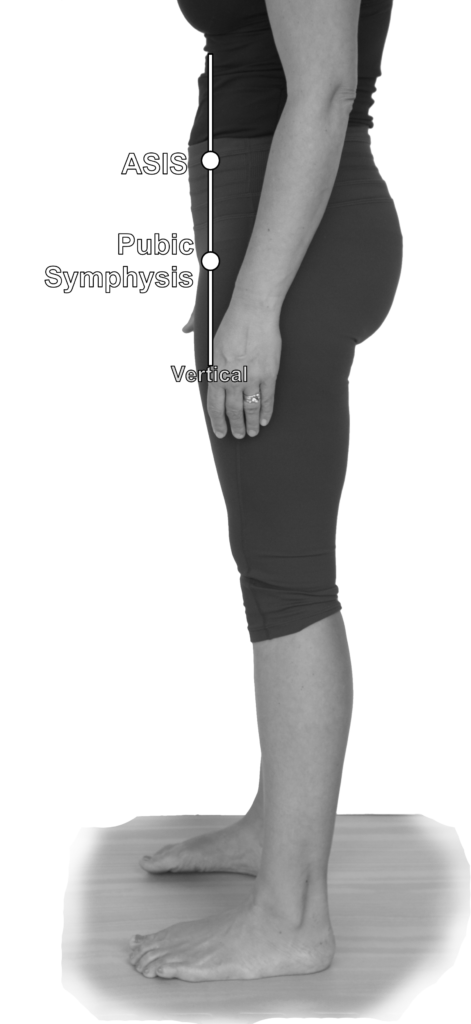

Side view

The final part of your three-dimensional alignment check requires a third point: your pubic symphysis, and for you to turn and evaluate yourself in the mirror from the side. The side view of a neutral pelvis will show the ASIS stacking vertically over the pubic symphysis, so that a plane containing all three points—both ASIS and your pubic symphysis—is vertical.

BACK TO THE QUIZ!

In the picture above, my pelvis is neutral, but my spine is not. The excessive curve you see is not because because my pelvis is tilted forward (it's not answer B); the swayback is created, in this case, by my rib thrust.

So, is this curve in the top picture C. hyperlordosis or D: hyperextension of the lumbar spine?

I'd say C, as hyperlordosis refers more generally to a deep curve but not exactly where it is and how it's made (similar to "swayback"). I would say Not D, because true lumbar extension would take my torso in a different direction than forward.

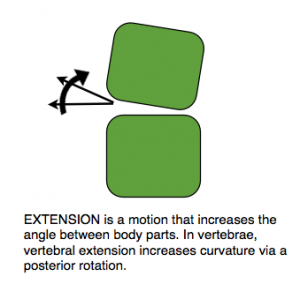

Let's say the vertebrae start from this position:

When vertebrae extend, it moves what's above "behind" neutral:

When vertebrae extend, it moves what's above "behind" neutral:

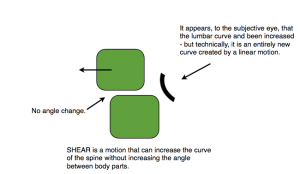

The spinal movement you can't see in my "swayback" picture at the top is created less by vertebral extension, and more by vertebral shear, a movement where surfaces slide past each other.

Vertebral shear, like vertebral extension, can also deepen the curve in the lower back:

Because of the attachments of the vertebrae, moving your ribcage relative to your pelvis would create a compound movement that blends shear and extension (it doesn't have a name yet, but then again, our anatomical language is pretty lacking when it comes to describing complex, compound motions).

My swayback, as pictured above, is made by the backward rotation/displacement of my ribcage. This vertebral motion moves my lower thoracic vertebrae forward relative to the lumbar vertebrae below, creating a deeper curve that looks suspiciously similar to a curve created through hyperextension my spine. While they're both lordotic curves, these two curves are different when you consider the orientation of all the parts.

Shear or extension? sounds like an argument in semantics, but it's not. These are two entirely different physical motions that require entirely unique corrections.

It's easy to use swayback and anterior tilt and hyperlordosis and lumbar hyperextension interchangeably if you don't start with an objective, mathematical definition of neutral pelvis and definition for a neutral ribcage. Lumbar curve is created by how the pelvis and ribcage are positioned relative to each other in space, so it's important to know where these bones are relative to your curve.

The leg and neutral pelvis

As I said above, "neutral" is less about the position of one bone and more about how parts relate to each other and to the ground (read Move Your DNA for more on loads). Leonardo, this is why I love you so much; you've paired a neutral pelvis with a neutral leg (vertical!).

Neutral ribcage

We use the landmarks and the alignment of neutral pelvis in order to put it on a grid for accurate measurements and we do the same with the ribcage. Start by finding a straight, vertical leg and then tilt your your pelvis as described above. Now it's time to get your ribs into position to allow for a neutral lumbar curve. ("Neutral" is really a whole-body thing, you see.)

Aligning your ribs to your now-neutral leg and pelvis is simple. Lower your ribs down until the lowest points on the front of your ribcage sit in the same vertical plane as the points of your neutral pelvis.

This ribcage movement will also adjust (decrease, in this case) the curve of your lumbar spine.

Spinal curve is a tricky thing, because although there is no absolute value of curvature that is appropriate for every person, there is a curve relative to one's body parts when standing that is part of good vertebral loading. It's confusing when talking absolute vs. relative measures because although not everyone needs to be at X° of lumbar curve, this doesn't mean that any degree of curve will do. This is why anatomical neutral is great; you get a curve that suits your particular anthropometric dimensions.

P.S. When you measure your body in this way, you might find an issue in your back is tied to how you move your upper body or legs—something located a distance from where your issue is manifesting. Read Are You A Rib Thruster for more on that.

P.P.S. Does anyone else think it's weird that my one-day old baby looked exactly like Bobby Flay?

Dig deeper into the concept of alignment in Move Your DNA and the way rib-thrusting movement affects pressure and issues like diastasis recti, in my book Diastasis Recti: The Whole-Body Solution to Abdominal Separation. Find more movements to free up pelvic motion in our Healthy Pelvis DVD and in the online video course Nutritious Movement Improvement.