Change isn't easy, or pain-free, or even without consequences, but still, it needs to happen in many areas of our lives.

In light of the research on the negative impact sitting has on our health, how loads to the body shape human development, and recent insights into stillness, learning, and the brain of a child, many have requested I come speak at their school's PTA meetings and help motivate their schools from sitting, or create some sort of book that can be shared with their school administrators. But since there's only one of me and a zillion of you, I thought I'd share some notes on a keynote I gave at an educational conference this summer so you could share it as a first step.

In my talk (not on curriculum or cognitive development, but on sitting), I acknowledged that in many cases curriculum-as-we-currently-do-it depends on stillness in kids. My message is not trying to counter what is required for passing tests, but addressing what is essential for the whole child, for the child's whole-life, and for the whole-community of which the child-then-adult is a part of. It's big picture stuff, and I realize it. I'm not here to nitpick the educational system, but take a broader look on how sitting has permeated the culture as a whole.

Here are my notes:

THINKING OUTSIDE THE CHAIR by Katy Bowman, M.S.

Our mechanical environment is constant, meaning there are forces constantly at play--shaping our bodies into a structure we will call on in the future. Unfortunately, the set of forces we modern peoples tend to create results in a structure not well-suited for basic biological functions like digestion, respiration, procreation, etc. Issues with our structure tend to arise in our thirties and forties, thus perpetuating the idea that the ailments we have are a sort of “wearing out” of parts, but actually the ailments we experience now, as adults, began long ago. For example, osteoporosis--a disease where bones become less dense (more fragile) and prone to fractures and breaks--is now known as an issue stemming from peak bone mass not achieved in childhood.

Millions experience these ailments of affluence--illnesses that arise in cultures with abundant, poor-quality food and poor movement habits--yet expensive research showing (yet again) that we need to move more is rarely integrated in to real life, where the large bouts of inactivity occurs.

Many think “Hey, I walk a mile every day,” or “I ride my bike to work!” and that’s fantastic. But in these cases we are attempting to achieve, with a bout of exercise, the effects that all-day movement has on the body. In the same way eating one meal’s worth of calories (700) a day doesn’t fuel us in the same way a full 2500 calories does, our approach to exercise--an hour a day--is the equivalent to movement-starvation.

Even with competitive athletes, the latest research shows that people can be both active and sedentary. Do the math. Even if you exercise an hour a day, seven days a week, your total movement time equals a whopping 420 minutes out of 10,080 minutes in a week, or about 4% of all time spent. The rest of the time, the 96% of your weekly minutes, exercisers and non-exercisers alike sit--in their chairs, at their desks, in front of their books and computers.

I, like you, think a lot about my physical positioning throughout the day. Or, perhaps you don’t consider your own posture all day long but you think about the positioning of your students or the alignment of children in general. The positioning of the human body is critical, as it is the position of parts and how these positions are utilized throughout the day that create the forces that end up shaping the body. However, most of the parameters for “good” positioning stem from ergonomic science, which does not necessarily mean what is best for you and your body.

The trouble with using ergonomic science when selecting optimal posture is that ergonomics is not the scientific pursuit of what is best for the human body but the scientific pursuit of how the human body can be positioned (as in one position for 8 or more hours at a time) for the purpose of returning to work the next day, and then the next and the next and the next, until retirement age. Finding an optimal working position, then, is not about your long-term health as much as it is about your production value over a short period of employable time.

It is critical that we read the fine print on the ergonomic prescription label: WARNING. BEING STILL IS DETRIMENTAL TO YOUR BODY. Or said another way: There really isn’t a “best” way to sit for the body, there is only a way to sit that loads the parts damaged by chronic sitting in a less-damaging way; and to focus our energy on optimal stillness is like researching for the most nutritious 600 calorie diet instead of solving the problem of being underfed.

Defining, more clearly, the terms posture and alignment can be helpful to remind us why it’s not a position that we are after, but a set of forces under which the body responds well.

Posture: the way in which your body is positioned when you are sitting or standing.

Explaining posture a bit further, posture is the orientation of parts. You quantify posture by measuring how parts are positioned relative to each other as well as how they’re positioned relative to the ground. Or maybe it’s easier to think of the body on a grid where you can plot the parts on this graph.

Alignment: the proper positioning or state of adjustment of parts (as of a mechanical or electronic device) in relation to each other.

Both posture and alignment have to do with positioning, but they differ in that alignment’s definition includes the word proper. It is this idea of “proper” that sets the two apart. Proper doesn’t mean imply better in a condescending kind of way, but is defined as “of the required type; suitable or appropriate.” Just as there is a proper diet for the human (or the horse or snake or the tiger), there is a proper alignment.

Just as a proper diet is made up of a vast array of nutritional components, proper alignment is made up of nutritional loads--varying, unique deformations (think: micro-deformations) to the physical structure (called loads) that result in a particular genetic expression that deems your structure.

If you drive a car you’ve probably had to have your wheel alignment (and not your wheel posture) adjusted at some point. In this case your mechanic is not finding the most attractive position for a wheel. In fact, wheel alignment is not about static positioning at all but how, once moving, the interaction of a system–the road, the wheels, the tire, suspension components, and other stuff that I know nothing about–doesn’t inflict excessive damage on any single part making up the system.

To find optimal wheel alignment, the mechanic must consider the material fatigue points, the forces created by the speed, terrain (does your vehicle go off-road?), tire pressure, etc. In short, alignment includes the consideration of forces. Or said another way, posture is the visible orientation of parts, while alignment encompasses the invisible forces created by particular movements.

This is all a long way of stating that good alignment requires movement. Without movement the forces your body needs cannot be created. This isn’t to say that we can’t create a better load-profile while being still. We can and should still work to maintain good sitting alignment, but there is a larger issue at hand when it comes to children’s health--both now and in the future--that can only be solved through movement. There is no static position that optimizes human development.

It is a waste of money and time to research the epidemic of poor health in children if we fail to acknowledge the role parents and educators play in cultivating stillness in these young humans. We must challenge the deeply seeded belief that children have to stay in their chair in order to accomplish educational goals or be perceived as well-mannered.

This brings me to the classroom.

We don’t tend to think of it this way, but if one were to quantify “skills practiced” in the classroom, ages 5 to 18, the winner of “Most Time Spent” would not be reading, writing, science, mathematics, music, physical education, critical thinking or art. The winner would be sitting.

I’m not trying to be funny here, but totally clear. Learning shapes both the mind and body of a child and the most-frequent input in our modern world is mechanical, and in this case it is the loads created by the modern chair. Our structural adaptation to sitting comes in handy, I suppose, as most adults will call on these cellular (as in cells of the body, not mobile phones) adaptations created in childhood to support their most-frequented position as an adult--also sitting.

It is at this point that I’d like to propose that, for the rest of the time you spend reading this document, you sit on the floor. I do so because I’d like you to experience (perhaps) the internal resistance we all have, quite naturally, to change. To sit on the floor is to demand your body expend energy: increasing muscle mass, and tissue length, shuttling more blood and taking in more oxygen. All because of how and where you sit. I’d like you to experience your own personal resistance to a chair-free experience because it is you, reading this paper, which will end up shaping a child’s mind and body via your own personal relationship with the idea. This is how memes work.

A meme is an element of a culture or system of behavior that may be considered to be passed from one individual to another by nongenetic means, especially imitation. It is a vicious cycle of behavior that, in this case, goes something like this: The adult-preference for a chair shapes a body, which then shapes the culture (bucket seats in everything!) which then shapes the children who start sitting in them, and at younger and younger ages.

I propose that a simple, inexpensive (as in “free”) solution, is to get chairs out of the classroom. To utilize many postures to get work done, with the cycling between them creating necessary forces. To move more throughout the day and to build lessons around movement--and not make movement something separate from life or learning.

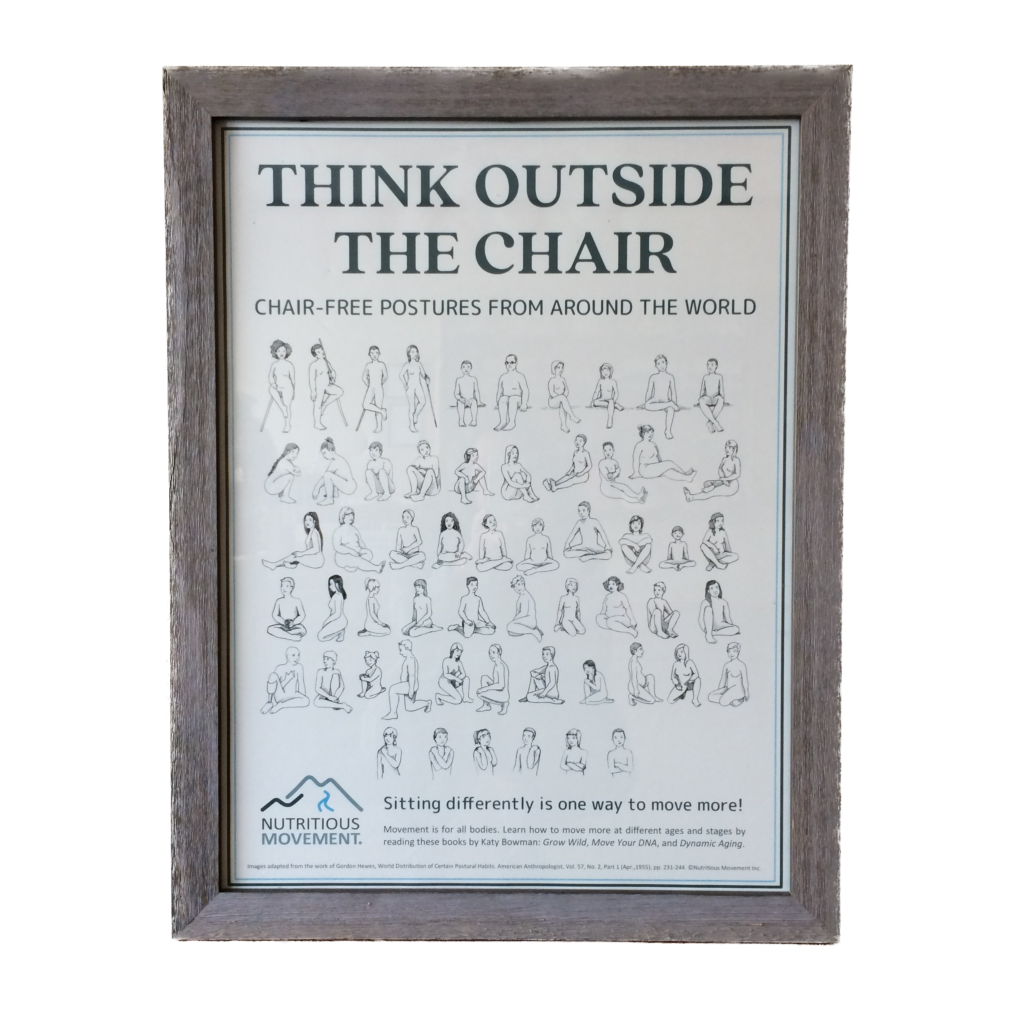

Anthropologist Gordon Hewes spent time cataloging the postural habits of the world, noting that the way we hold our body is a sort of non-verbal communication, displaying what the individual is “saying.” Adapted from his research, here is a recreation of how the rest of the world takes their rest time. [I'm putting a pic of the Think Outside The Chair poster so you can see some of the poses.]

I would like to amend Dr. Hewes work by saying that our bodies are not only communicating on our behalf, but on behalf of our culture. Woven into the shapes we assume when happy, sad, proud, and ashamed are the shapes we have been bequeathed by those before us, through a subconscious, non-genetic hand-me down process. We are wearing the physical hand-me downs of thoughts and emotions of those before us.

The time has come to acknowledge that what we are passing down is not beneficial, or maybe is no longer beneficial. As for me, I would like to collectively inform our children that their movement is not only okay, but good, healthy and fundamental. I believe removing chairs from classrooms would be the simplest step we could take as parents and educators to produce the largest change in trajectory of health in our culture. The simplest away of allowing our children--and their bodies--to “speak” for themselves, now and in the future.

***

In my live talk, I actually had all the conference participants (sitting, like good students) get out of their chairs. Get out of their comfort zone. And, it was uncomfortable. Not just for them, but for me. They didn't like me all that much in that moment if that makes sense. OR at least they didn't like me for asking. It was kind of like asking 100 sullen teenagers to take out the garbage. And a funny aside -- when I turned this article in to the conference manager, she read it and then sent it to the note-binder printer. Then one called each other to see if she sat on the floor when I made the no-sit request. Neither of them had.

So, my point is this: How can we, the keepers of the behavior/the shapers of the behavior (and the furniture) of the future, expect our little animals (read: learn via modeling) to get out of the chair when we cannot-but-really-can-and-just-don't? What if schools could run just fine without chairs and without stillness, but that the transition would take a ton of work elsewhere? What if the problem is our own inertia? What if I am the problem? How am I the problem?

Here are the concluding slides from my presentation:

1. Listing some of the literature headlines, I asked, "In light of this information, who is responsible for adjusting our behavior?"

ANSWER: I am responsible. I am "the school." And so, this is what I have done to take responsibility for the issue (among other things).

You, my friend, are also "the school." If you feel sitting too much is a problem, here are some things you can do right now.

We--all of us--are "the school." We cannot ask someone else to be interested, aware of, or take action to remedy an issue we ourselves are actively playing a role in.

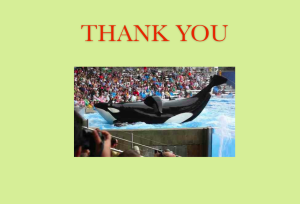

Then, I ended with this, which looks like a non-sequitur, unless you've read Move Your DNA or this blog post (Disease of Captivity).

#thinkoutsidethetank #getoutofthetank #MoveYourDNA

Sorry for the hashtags. I CAN'T HELP IT!

More reading on sitting in classrooms:

CNN: Why do we make children sit still in class?

Australia Heart Foundation: Sitting less for children

Education Week: Give students time to play.

The Washington Post: Why so many kids can’t sit still in school today

The Atlantic: Exercise Is ADHD Medication

Hewes, G.W. 1955. World Distribution of Postural Habits. American Anthropologist. (April): 231-244.

Hightower L. Osteoporosis: pediatric disease with geriatric consequences. Orthop Nurs. 2000 Sep-Oct;19(5):59-62.