March 5, Katy Bowman and Jill Miller will be leading a live, online masterclass, all about breast and chest movement. More details at the end of the article.

Breast discomfort and pain show up again and again in the top reasons people shy away from exercise: they’re fourth after energy/motivation, time, and health. There are many factors at play; I’m here to talk about the mechanics and how we can think about loads and what’s going on in different parts of the breast and the surrounding parts when we move.

Breasts move all over the place. Not only up-and-down and side-to-side but also in and out. The breast movement you see, and more importantly feel, when being active is movement that can be broken down into these three planes.

While breasts can move in three planes at once, their movement is not necessarily equal in all directions.

Breasts come in many different shapes, sizes, and stiffness, and each of these impacts how they move. To keep things simple, think of it this way: the heavier the breast, the more the load and movement created in each of these directions. Likewise, the lighter the breast, the less movement and the smaller the load.

Different activities move breasts differently. The movement of the breast depends on the movements that make up the activity. How might breasts be moved by hula-hooping? Jumping rope? Downward dog in yoga?

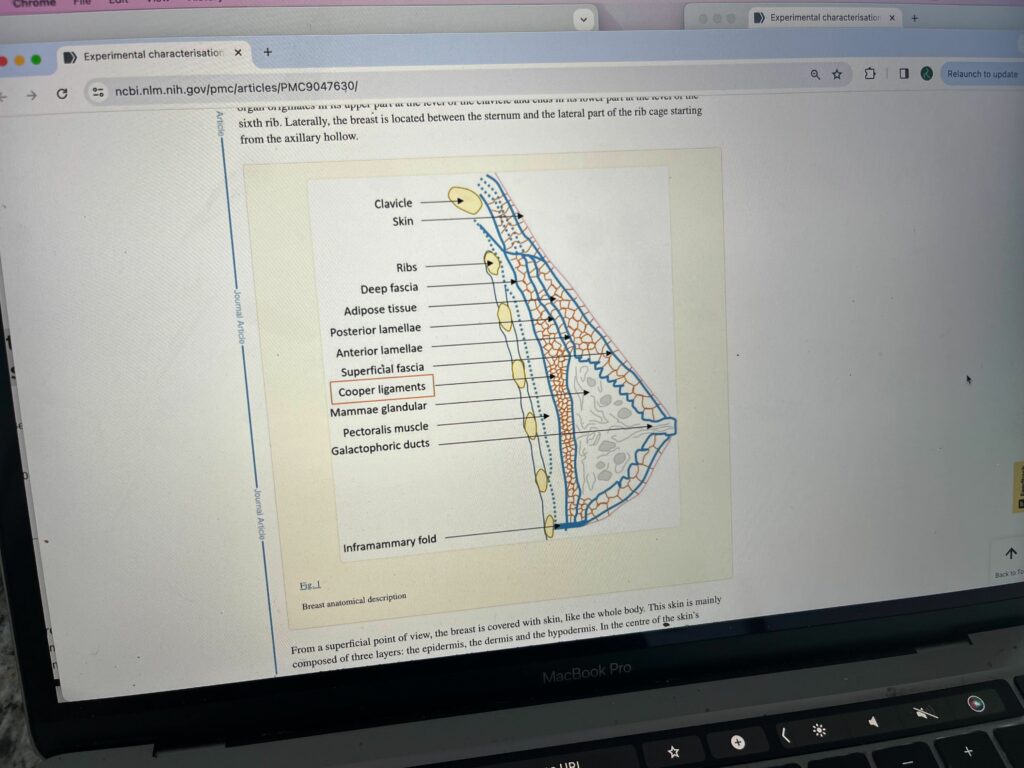

The breast shape is created by what’s inside and deep to the breast. Each breast is a set of layers, and the layers are supported by Cooper’s ligaments—bands of strong, flexible, fibrous connective tissue. They not only connect the breast to itself, they also connect the breast to the wall of the chest.

But, the breast isn’t hanging on a ligament like a pumpkin dangles from its stem. Breast ligaments are distributed throughout the breast—little threads that create pockets for glandular tissue and ducts.

Check out a diagram from this paper: Experimental characterisation and modelling of breast Cooper’s ligaments.

The orange threads are the ligaments, the blue lines are fascial tissue, and this white space bordered by the dotted blue line is the pectoralis muscle.

To sum up, the parts of the breast that support the breast from the inside: Cooper’s ligaments, pectoral fascia, and the pectoralis muscle.

Breast shape changes over time. Some changes are due to changes in anatomy relating to our stage of development. When breasts mature, they grow glandular tissue, ready to generate milk if activated. During another developmental stage—menopause—the body starts getting rid of the milk-producing lobules of the breast in a process called lobular involution. The loss of matter creates a longer and thinner (a more dropped) breast shape, called breast ptosis. Picture the toe-space of a sock stuffed with an orange. If you remove the orange, or replace it with a smaller one, the toe sock will droop, not because it’s “stretched out” but because some of the tissue that created the previous shape is now missing. P.S. You have lots of globules in the breast, not one, so it’s actually less like a sock with an orange and more like a sock full of grapes becoming a sock full of raisins.

There’s nothing wrong with the breast when this happens; it’s the shape of the breast that goes with this stage of life. Menopause can often be associated with an increase in fat mass, some of which could end up in the breast area. This can increase the overall size of some breasts, meaning you get larger, droopier breasts. (If I had more time, I’d write out my grandma’s favorite joke about breasts as hanging baskets of flowers here, but I don’t, but just know that I could and it's hilarious and makes me laugh every time.)

That all being said, not all changes in breast shape come from mass changes to the inside. Other factors that can affect if breasts “get lower” include: the upper back rounding forward, poor tone (tension in the relaxed muscle) of the pectoralis, history of smoking, significant weight loss, multiple pregnancies, and connective tissue disorders.

There is research on chest and other upper body exercises to improve chest pain, but nothing on how they change breast shape. For sure, strengthening your pectoralis muscles won’t affect droopage from most of the factors listed above (building muscle isn't going to replace the missing orange that once lived in your sock...). Still, hyperkyphosis (upper back rounding) and low pectoralis tone will both mechanically lower the breast, so working on these areas doesn’t have to be in vain, especially as anything you do for the breast is what you need to do to nourish the shoulder and chest (ribcage) joints as well.

Bras support the breasts externally. Bras are a CATEGORY of apparel, just like shoes. You can think of bras in the same way you’ve learned to think about conventional and minimal footwear—there’s a range of support to choose from. Some styles reduce breast movement to almost nothing (lock 'em down!), some offer just a little support, and there’s many steps in between.

Some breasts move way more than others, different activities move breasts way more than other activities can, and when you pair breasts that move a lot with activities that create a lot of movement, you can wind up with discomfort. Discomfort could be straight-up pain, but it can also be a breast falling up and out of a shirt when you're practicing an inversion in yoga. Personally, I like a bra that has a “roof” on it when inverting in class. In this case, my breast movement doesn’t hurt, but I don’t like spending time constantly putting my body back in its clothing. But I might not care about this when just doing headstands alone, so keep in mind we each get to determine our personal support needs depending on the scenario.

Below is a short video tour of the different bras I choose from (brands listed below). Just like my minimal footwear rack, I have a range of styles that offer less to more support, so I can get dressed depending on the way I feel and the activity I’m going to do. It really helps to think about bras as you do footwear, and how you determine when you’re going to wear shoes or not.

We can also be aware of over-supporting. Breasts are moveable bits of the body and preventing their movement (i.e. locking them down) all the time can leave them undermoved. Bra research using EMG has shown that, when running with less supported breasts, pectoralis muscles contract more compared to when they’re more supported. But, there can be more pain when running in this less-supported situation. When the upper body has to use muscle to support the chest, it uses those muscles more—and we want that. But it also could be that heavier loads (from heavier breasts or even smaller breasts being accelerated more by the bounce) during running isn’t the place for less support. Maybe your breasts can get their movement in lower-load scenarios. Again, it’s like minimal footwear. Sometimes you’re fine with less, sometimes you need more, and this need fluctuates depending on the activity, the location, and your body’s needs that day.

If you’re interested in learning a bunch of different exercises for the muscles and fascia of the chest and breast, check out my upcoming live, online masterclass with Jill Miller—A Breast and Chest Masterclass: Supporting the Ins, Outs, Ups and Downs of Breast Movement—on March 5 (recording included if you can’t make it live). More details here.

Bra brands: Pansy, Sweet Skins bralette; check out Title Nine and Athleta for bras designed with a variety of activities in mind.