This article from 2014 has been lightly edited and resources updated in 2020. If you're looking for more on the pelvis, find our overarching movement philosophy and how it relates to pelvic issues, as well as more pelvis and pelvic-floor articles, exercises, and recommendations at “Our Best Healthy Pelvis Resources.”

This is a uterus. Kind of.

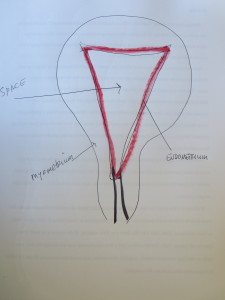

Just like a lasagna, the uterus is an organ made up of many layers. The outer-most organ wrapping of the uterus is the peritoneum. Inside of this thin wrapper are two meatier layers, which are, in turn each made up of additional layers, so really there are five layers and I don’t know why they don’t just say five instead of two.

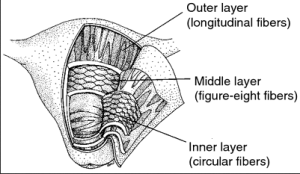

The thickest layer of the uterus is it's middle, muscular layer—the myometrium—which creates the uterus shape I think resembles an upside-down gourd. Like a gourd, the uterus is hollow inside (unless it's currently occupied). The myometrium consists of three separate layers of smooth muscle, each layer containing fibers running in a unique direction—right to left, up and down, and crisscross—a series you see over and over again in the body (e.g. the layers of your abdominal and rib-moving muscles are oriented like this as well).

Image from the Free Dictionary:

The innermost layer of the uterus is called the endometrium. The endometrium is the non-muscle part of the uterus and is understood to be the the part that sheds each month during a period. But we don't shed the entire endometrium—only a portion of it.

The endometrium also has two layers (see light ranting above). The bottom layer sits against the muscle layer and is called the stratum basalis (base layer). This layer of the endometrium does not shed during your cycle but is responsible for re-growing the innermost layer of the uterus: the stratum functionalis. The stratum functionalis layer is what's shed every month and if you're like me you want to know: HOW DOES THAT SHEDDING HAPPEN? Don’t you want to know? I mean, how does it shed? Why does it shed? WHAT’S ACTUALLY BLEEDING?

Here’s how it works. Right before you get your period, blood vessels to the endometrium contract, shutting off oxygen to the lining which—as weird as it sounds—kills the lining by starving it of oxygen. In response to the dying tissue, white blood cells (WBCs) are released to process and remove the now-dying functional layer of the endometrium. This process is called desquamation, which means to scrape the scales off a fish. Nice. You already know that your body, like a snake, is constantly desquamating, right?

The WBCs secrete digestive enzymes that break the dead tissue away, a process that also removes cells of the blood vessels just beneath the dying lining. These freshly exposed blood vessels on the surface are what is bleeding during your period.

But the WBCs don’t digest the entire stratum functionalis; there are “stumps” left here and there. I imagine a forest burnt almost all the way to the ground, but not entirely. And, just like a forest after a WBC "fire," endometrial repair (re-growth) begins immediately. Like berry vines and ground cover pop up from what continues to live beneath the forest that used to be, cells that will become the new stratum functionalis spring up close, at first, to the left over stumps, and then spread out to create an entire new forest floor (er, the lining of the uterus) in a matter of days.

Now, let's talk about the range of menstruation experiences, which include Heavy Menstrual Bleeding and painful periods (dysmenorrhea).

Going back to the step where the endometrium decreases oxygen to the shedding, this decreasing oxygen stimulates the production of a protein called hypoxia inducible factor one (HIF-1). Hypoxia Inducible Factor is what gets the “uterine forest” re-growing, but amounts of HIF-1 produced seem to vary between women. The more HIF-1 you produce, the faster you repair and the less you bleed. The less HIF-1 you produce, the more you bleed. (Not really a side note, because I think it's important: While I haven't seen mention of hyperglycemia and HIF-1 with respect to menstruation, I have seen literature on hyperglycemia and its negative impact on HIF-1 performance in general wound repair. File under food for thought.)

From Epidemiological Reviews, The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Dysmenorrhea:

Dysmenorrhea or painful menstruation is defined as a severe, painful, cramping sensation in the lower abdomen that is often accompanied by other symptoms, such as sweating, headaches, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and tremulousness, all occurring just before or during the menses (1).

As a member of this species, and a menstruating one at that, I find the prevalence of primary (not occurring with another known pelvic pathology) dysmenorrhea and the medicine necessary for a baseline movement problematic.

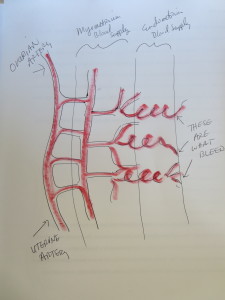

As I’m writing about in my upcoming book Move Your DNA (2020 update: it's done!) , the way we move—or don’t—impacts our body, head to toe. Menstrual cramps have been associated with the temporary reduction in blood flow to the uterus (necessary to kill the lining). But what doppler radar shows is those with primary dysmenorrhea aren't only having problems with the blood flow to their uterus during their period, the blood flow to their uterus is low all of the time. The time of the month where blood flow naturally reduces is merely highlighting a problem with uterine blood flow as a whole.

What makes blood flow to various parts of the body? The simple answer is "the heart" but more complexly, the muscle activity of you moving around moves your blood around more specifically. As with any issue, consider how you move. Not just do you move or not, but how. How your body moves is part of how your body works.

Want more on periods? Listen to Move Your DNA podcast Episode 50, Movement, Period read Menstruation is a Movement and Aching for an Answer.