The new Nutritious Movement Center Northwest is open and you're all invited to class!

I wanted our all-day grand opening event to be instructional and dynamic and to be accessible to all bodies.

I wanted our all-day grand opening event to be instructional and dynamic and to be accessible to all bodies.

I also wanted to give an experiential explanation of what the Nutritious Movement® approach to exercise instruction is all about.

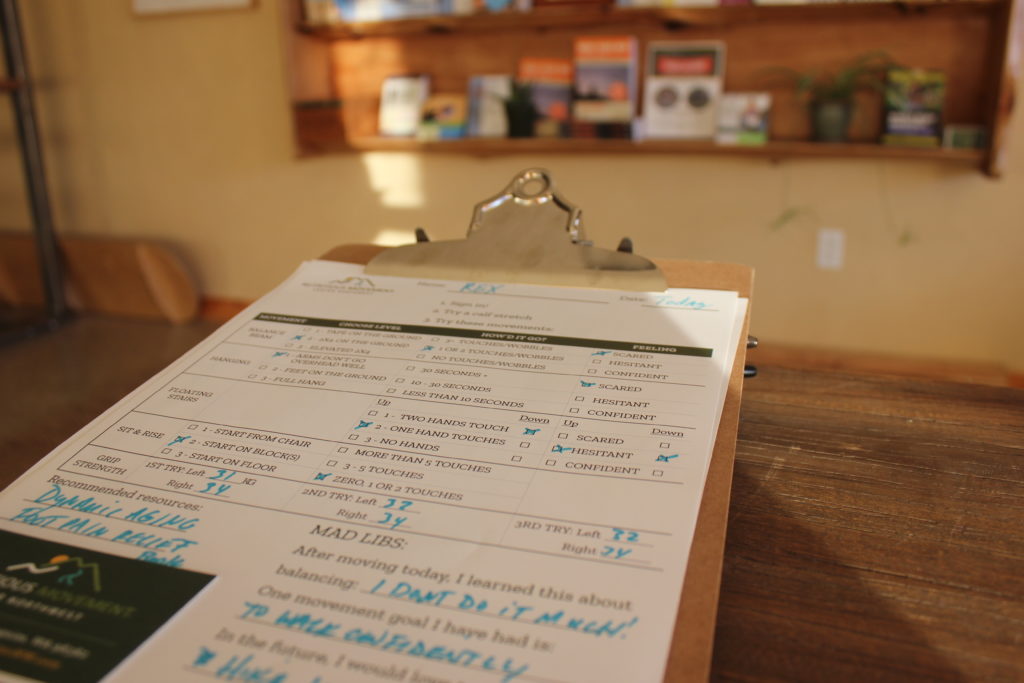

We created a handful of stations where people could observe how they were moving. Observing yourself move is a simultaneous yet separate act from the movement itself—moving is one skill, observing it another. Seeing, clearly, how we move can be tricky because we tend to pick and choose where we observe. I prefer the use of quantitative analysis, not because I'm a data head (I'm actually the opposite) but because it provides a more correct/less biased picture in many cases.

The movement stations were pretty simple tasks, like getting up out of a chair or off the floor, walking a thin line or 2X4, walking up and down an unstable set of stairs, measuring grip strength or seeing if your hands and arms could support your weight. We provided forms to record observations and visitors could take a station or leave it.

The movements were pretty simple—the measure of touching an arm or leg down, but we also wanted to measure how they felt about a move: scared, hesitant, or confident. I did some work in graduate school on the fear of falling as an independent risk factor for falling, so paying attention to how you feel about moving is incredibly important. One could actually be fearful of movement first, which then results in the regular choice to move less day to day. For this reason I find understanding fear as it relates to movement a very important part of one's personal movement restoration project.

Here are some of the stations we set up as well as a little on why I chose them, and how you can recreate some of these at home.

Grip Strength

Grip strength appears to be declining in our culture. It's not clear why, and it's also not clear why grip strength correlates to increased rates of all-cause mortality, quality of life, and mental health (search "grip strength" and any of these terms on Googlescholar because a single linked study or two won't be a robust enough read). The good news is, understanding why grip strength correlates to overall well-being is not necessary when it comes to improving the strength of your grip.

A hand dynamometer (a tool to measure grip strength) is not a practical piece of equipment for in-home use. Want to know the force of your grip? Your local university or physical therapy office likely offers this test.

At our event we posted grip strength charts so participants could get a sense of how they compared to their peer group, but mostly we measured grip strength, taken while sitting in a chair, to correlate it later to the experience at the hanging station.

Hanging

Hanging is a great for strengthening and mobilizing the upper body and torso. This move is made up of the movement of many smaller parts that don't get moved much on the computer, i.e. where our hands are most. By hanging you challenge your grip, and all the parts (muscle, fascia, bones, nerves) that make up your hands, wrists, elbows, shoulders, ribcage, ribs, waist, spine, and hips. ONE MOVE TO RULE THEM ALL, indeed.

Recreate this at home: Find a bar or branch and see if you can

1) reach your arms to the bar (no? Check out this upper body exercise program)

2) hold yourself while supported, i.e. your legs still touching the ground

3) hold yourself with your legs up for 30 seconds

4) hold for 60 seconds.

There are many reasons someone can't hang. Grip strength being lower than what your body mass requires to carry it is one reason, but before we even get that far, getting the arms overhead is often a problem. For this station one could measure their hanging skills as "arms don't go comfortably overhead."

In this case we could offer simple exercises like the Doorway Reach (pictured below) and the Thoracic Stretch as simple, inexpensive, do-it-lots-of-times-each-day ways to work towards the larger skill of hand, wrist, arm, shoulder, upper spine, and trunk/core mobility and strength. These stretches are all elements of a hang.

Balance

Working with thousands of bodies provides one with thousands of hours of valuable observation. One thing I've learned in the last twenty years is we don't realize we've lost the ability to balance because we don't do anything that requires it. People are stunned when they realize they can't walk on a line of tape without falling off.

We created three options (scale to your comfort level!) that measure essentially the same thing: Can you adapt your gait to a provided surface? Walking a line of tape is pretty risk free, so it reduces the fear of falling (and remember, we also wanted people to check in with how they felt about the obstacle itself). How many times did you touch down or "fall off"? How many big almost-falls were you able to recover from (also a great skill)?

Recreate this at home: Walk along

1) the edge of a carpet, seam on the floor or a line of tape (about 15'/4.5m)

2) two 2x4s

3) elevated 2x4s down and back (staying on while you turn around on the end)

and note any losses of balance (any part, hands or feet, or hips if you're against a wall touching down) as well as almost losses. Note how you feel about the obstacle: scared, hesitant, or confident.

Here's what's amazing: People get better scores in minutes, simply by moving this way a few times. Doing the thing is what helps you get better at the thing! This is what lies at the heart of training: when you practice moving in complex ways, you're prepared and resilient when challenges arise unexpectedly.

If you never walk in places that dictate gait adaptations, you lose the ability to do so. Our takeaway homework for this station was to put a line of tape down a hallway (at home or work) you frequent. This builds more complex movement into your environment so it doesn't have to be added to your exercise time. You were already walking down the hallway; might as well make the walk more nutritious.

P.S. Adding height makes things more complex because as movement is perceived as riskier, it can invoke fear, which can change the mechanics of how you move.

Getting up and down

There is a now-famous Sit and Rise test, but I didn't want to link the grand opening with a "Hey New To Movement-ers, this is a good measure for mortality. Your score dictates how long you'll live! Have fun, no pressure!" kind of vibe. Instead I created something that provided similar observations about the mobility and strength of the feet, ankles, knees, hips, and spine, but was scaleable to the individual.

Participants could choose to sit in a chair or on a bolster or block (each one is lower than the other). They stood up and sat back down to see how they did it. Did they need a ton of momentum, have to fling arms or the torso, use their hands on the floor or stumble as they came up and back down again? Offering the scale allowed everyone to work from their level and notice their current movement strategy. Once they had measure of how they did it, they could try to get up differently to change the score, i.e. moving more parts of their body.

Recreate this at home: Start sitting on

1) a chair

2) a bolster or stack of blankets

3) a yoga block/book

4) the floor

Stand up and sit back down again, counting any time your hand touches down (including pushing on your legs when rising from a seat), and stumbles/losses of balance, and noting if there was momentum (and where it was coming from). How did you feel about this movement: scared, hesitant, or confident.

Tying it together

At the end was a little "movement mad lib," an idea gifted to me by a workshop attendee last year. We left a little fill in the blank on their data card so individuals could mull on what they learned or realized in the process.

Conjuring a movement goal and something movement related we'd to do in the future gives everyone context and a personal framework for exercise, corrective exercise, and assessment. It's not about what I see or value; it's about what you see or value for your life. Based on the feedback from the movement experiences and the self-declared goals about larger movement feats outside of class, we could better steer people to the practice of specific exercises, everyday movements, and environmental modifications that will lead them to the physical experiences they value most. And that's what Nutritious Movement is all about.