“By making the material understandable, approachable, and achievable, Bowman offers an outstanding and necessary guide to diastasis recti and many other abdomen-related issues. Everyone can benefit from these insights and improve their health in an empowered and proactive way.”—Foreword Reviews

2016 INDIES Award Finalist for Best Health Book

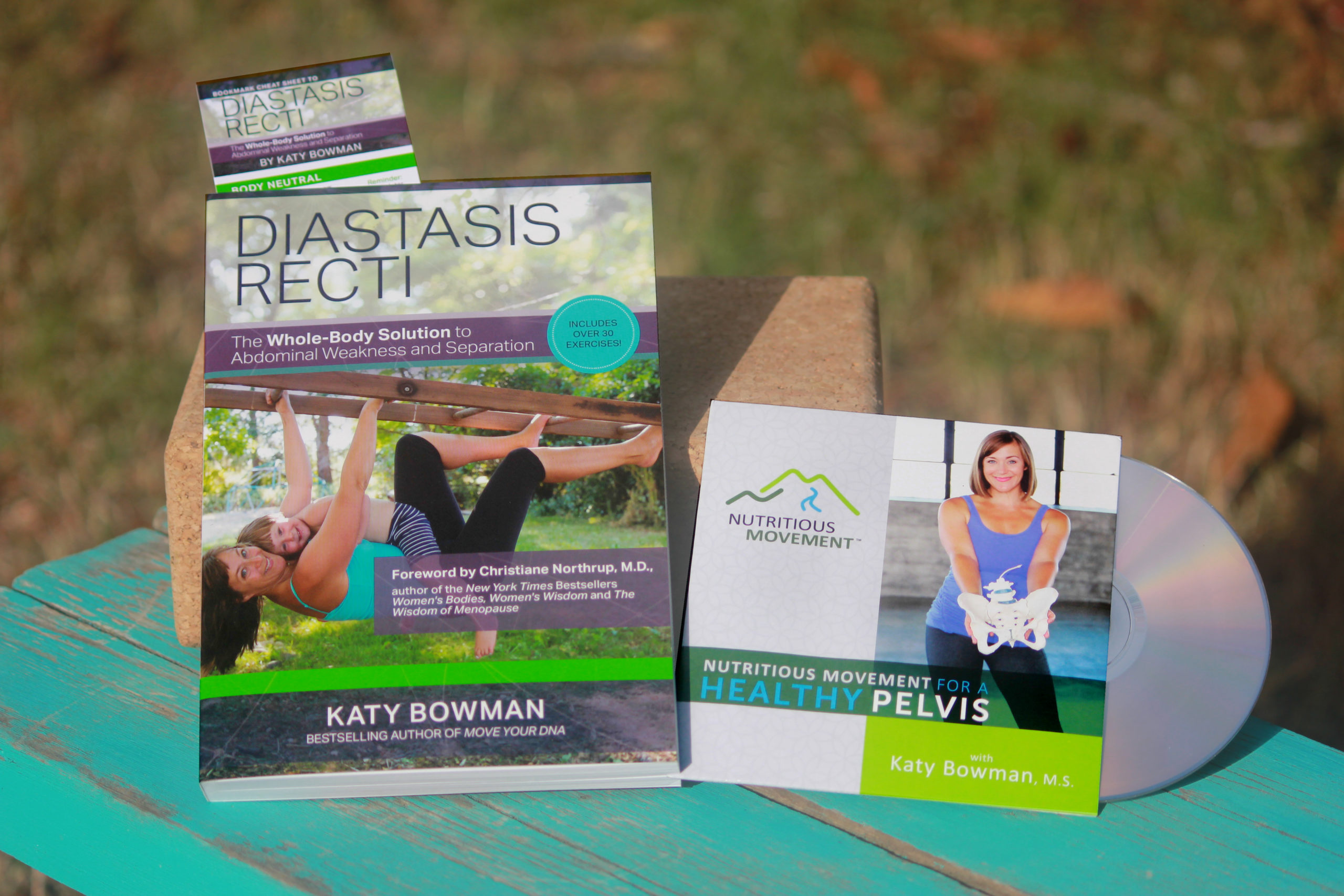

From Chapter 4 of Diastasis Recti: The Whole Body Solution to Abdominal Weakness and Separation. Sample exercise below!

Our modern habitat, for all the wonderful advancements it has allowed, forces us into a particular body geometry. Chairs, heeled shoes, computers, cars—the list goes on—have forced your body to adapt in a way that means when you get up out of your chair to walk around, a great load is placed on your linea alba.

Not the muscles of the core, mind you (those muscles are rarely loaded), but the connective tissue that can support you without expending energy. Ever wonder why you like to jut your hip out while you stand? Why you hold your hands behind your back? And why your pelvis rests in a forward position? These positions allow you to stay upright without making your muscles work.

The body’s innate tendency to conserve energy comes from a time when food and movement were more organically entwined. When humans spent most of the day moving and expending energy to find barely enough food to cover the caloric cost of finding it, “lazy” standing wasn’t a big deal. You weren’t going to be standing around doing nothing all that often. But when we move very little, our natural “lazy standing” tendencies are called on more frequently—and it’s the frequency of these lazy loads that can cause injury.

Slow, sustained loads in a certain direction can deform tissues in a manner from which they cannot recover. Mechanical creep (yes, I said creep) is the tendency of a material to deform slowly under a constant stress. The failure of a tissue in this case is called a creep failure. A disastasis recti or hernia is the result of creep failures. You could also say that these tissues got creeped out. (Or you can leave the biomechanist jokes to me and go about your business.)

The tendency to use our connective tissue to rest not only overloads the connective tissue, it under-loads various muscles. When you’ve been using your arms almost exclusively for activities (typing, driving, pushing a stroller) where they are positioned out in front of you, your shoulders lose some of their range of motion. In those few times a day when you do use your arms overhead—that rare tennis serve, putting something on a high shelf, or an occasional home-improvement project like painting the ceiling—the movement of your arms takes your ribs with them. Your shoulder has adapted to what you do most frequently, but what you do most frequently is not what’s best for your shoulder, or for the abdominal muscles that are displaced when you go to use your arms.

Were you living in an earlier time—when food and water were not readily available, let alone less than three feet from you at all times—your body would be adapted to a much wider range of movements. Your body would be stronger. Your body would not be collapsing.

Modern living does not require that we move, and to add insult to injury, it actually limits full use of our body. For example, a couch, although super comfortable, limits the full use of your ankles, knees, and hips. It sets the distance over which your leg and hip muscles can work. If you’re leaning against something right now, that something is doing the work your core muscles would be doing were that thing not there. We’ve effectively outsourced the use of our bodies to our stuff. And then when we ask our bodies to hold us up, and hold stuff in, they fail. Make no mistake, it’s not only the tissue that’s broken; it’s the habitat.

The most accurate answer to the question, “What created my diastasis recti?” is, “Your diastasis recti was created when the forces applied to your linea alba deformed it.” But I know that’s a biomechanist kind of answer and not really the answer you’re after. So, taking a step back: your body wasn’t strong enough to handle the loads placed upon it. Okay, there’s a simple solution for that. There are exercises to do and movements to add that can improve the strength and the balance of strength throughout your body. And now, taking another step back: your habitat is shaping your body and loading your linea alba when you’re not moving. This, too, is simple enough to remedy. We can change our shoes, our relationship with furniture, and how we set up our home and work environment. Don’t worry, I’m not going to tell you to throw out all the stuff in your current life. What I will do is help you discover the best in both your habitat and your body.

Try an exercise from Diastasis Recti!

SEATED SPINAL TWIST

• Sit in a chair with a neutral pelvis and your ribs down.

• Without jutting your ribs or tucking or untucking your pelvis, turn to the right and to the left without straining.

• Move to the edge of your range of motion, taking care that you’re not slightly moving out of alignment to go farther.

• Once you’ve done this a few times, hold to one side, practicing the active intercostal exhale for 5 breaths.

• Then twist back and forth a few times and hold the twist to the other side (ribs down), doing the active intercostal exhale again, for 5 breaths.

• Complete the circuit with a few twists back and forth.